|

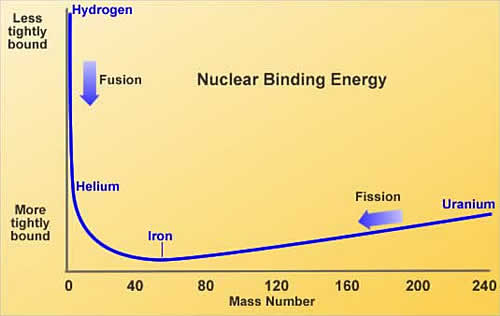

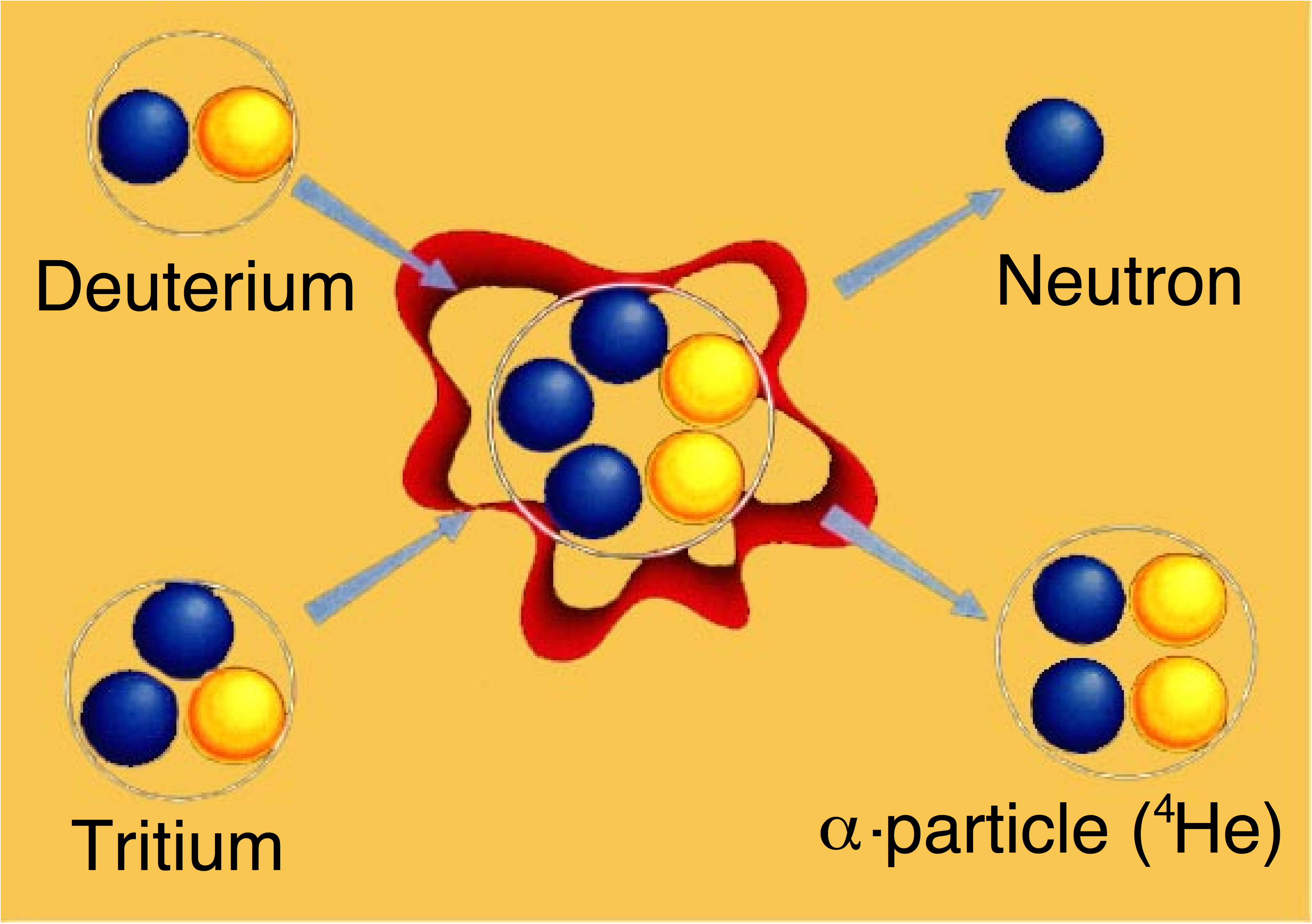

What Is Fusion? Nuclear fusion involves the bringing together of atomic nuclei. The atom's nucleus consists of protons (p) with a single positive charge and neutrons (n) of similar mass and no charge. The strong nuclear force holds these "nucleons" together against the repulsive effect of the proton's charge. As many negatively charged electrons as protons swarm around the nucleus to balance the proton charge, and the mass of the atom lies almost totally in the nucleus. The sum of the individual masses of the nucleons in a nucleus is greater than the mass of the whole nucleus. This mass difference (Δm), and the energy of the strong nuclear force (ΔE) binding the nucleons together, are related by ΔE=Δm.c2. This binding energy (a deficit) varies from one element to another. Because of the possible ways that nucleons can pack together, when two light nuclei fuse, the nucleons in the combined nucleus become more tightly bound together than the fusing nuclei. In other words the binding energy of the combined nucleus is higher than the sum of the binding energies of the fusing nuclei. This binding energy difference, between the individual nuclei and the combined, is released in the "fusion" process. A similar situation occurs when heavy nuclei split. Here the binding energies of the pieces can be more than that of the whole, and the binding energy difference is released in the "fission" process. These alternatives are shown in the figure.  (with permission ©IAEA) Thus in fusion the energy released per reaction, for example between deuterium and tritium, is about an eleventh as much as released in the fission of a uranium nucleus. Conversely, the energy released per nucleon involved in the fusion reaction is about four times higher than for those involved in the fission reaction. In the Sun and stars a chain of fusion reactions occurs which converts hydrogen to helium [68]. There are two chains, both having the same effective result, and which one dominates depends on the size of the star. For our Sun the proton cycle dominates.

The overall reaction rate is extremely low, but it nevertheless drives the universe due to star sizes and huge masses. The particles are held together by gravity long enough for sufficient reactions to occur. For instance, in the core of the Sun the temperatures is 10 - 15 million °C. Along with the extreme pressure (a quarter of a trillion atmospheres) and density (eight times that of gold), this allows matter to be converted into large amounts of energy. To make fusion on a smaller scale on earth, more probable reactions have to be used. A figure of merit for a reaction is the "reactivity" - the product of the probability of reaction and the energy delivered per reaction. As the figure below (for a given confinement capability) shows, the fusion reaction between two "isotopes" of hydrogen, deuterium (D) and tritium (T), has maximum reactivity at around 100 million °C (isotopes have the same number of protons, but a different number of neutrons). The next most reactive is D+D, about 40 times smaller, and D+3He, an isotope of helium, about 85 times smaller. The "catalysed" D+D reactivity value includes "side reactions" between D and the D+D reaction products, namely T and 3He.   For comparison, the reactivity of stellar reactions is 3 x 10-25 smaller than that for D+T. This large difference allows fusion power to be a possibility on human scales, but the removal of the large mass which allows gravitational confinement to work so well in stars means that different confinement schemes have to be exploited, and these have different conditions for their success. |